Compost is a biological inoculum or – concentrate.

Compost should contain a diverse range of:

- Bacteria

- Fungi

- Protozoa

- Nematodes

A mature compost will also contain worms, as worms eat microbes not organic matter.

Not all compost is compost

At G.U.F, we know that there are many materials that are passed off as ‘compost’. There are also many ways that ‘compost’ is made. Too often the supplier’s word that it will ‘be good for our soil and plants’ is taken without question. Some materials passed off as compost, even those with the stamp of approval of the Australian Standard, can be toxic to soils and plants. It is ALWAYS important to ask about the source of raw materials (feedstocks), the making process and its storage. If buying large quantities, insist on a signed copy of the compost batch analysis, including its microbiological composition. In any case, use your senses to make your own in-situ assessment – if it smells good and earthy with a mushroom overtone and is no darker than dark chocolate in colour with little or no original feedstock components evident, then it is likely to be a reasonable compost. Only testing and trials will confirm this – or use our consulting services if you want an independent opinion before committing to purchasing compost or mulch.

What is Compost:

- The most complex and diverse biological inoculum with active and dormant organisms each awaiting suitable conditions to actively contribute to the soil microbiological network. G.U.F recognises that Advanced Microbial Compost is essential for best results in soil and plant health management and Actively Aerated Compost Tea brewing

- A source of nutrients, its range contingent upon the feedstocks used in its making but having been converted into bio-available and un-leachable forms by the microbes performing the decomposition and transformation of the raw materials.

- A long term source of beneficial organisms that can beneficially affect the soil and plants for up to several years after application.

- For maximum benefit and value, must be made correctly and matched to the specific plant/soil for its biological and nutrient components. (If bacterial levels are high in soil and weeds already a problem, a bacterial compost does little to improve the soil or aid the tree/plant).

- Advanced Microbial Compost cannot and should never be misrepresented or confused with aged manures, mulches or less than satisfactory ‘compost’.

- Compost MUST exceed Australian Standard AS4454 base standards as a minimum, but even if it meets or exceeds this, there is no telling whether it will perform the job expected of it.

- It is ideally made by suitably trained persons who keep records, regularly monitoring temperatures and turning the compost (thermophilic) or manages the static or vermicomposts by recording the feedstocks used to build the pile or feed the worms.

- Finished compost of any type should not be hot. If thermophilic compost holds a high temperature (>35c), it is still composting and will limit nutrient availability and draw water away from nearby plants.

- Finished compost will reduce in volume by about half of the feedstocks used in their raw form. In the most part, very few of these feedstocks should be identifiable in the end.

- Though very forgiving, compost should not be stored in plastic or very large piles as it restricts oxygen exchange.

How do you know it is good compost?

- High biological diversity and balanced to suit soil/crop needs

- Pleasant earthy smell

- Sits at ambient temperature – no longer holds heat

- Has a good ‘feel’ about it

- Dark brown in colour

- Soil like in appearance

- Little or no recognition of the raw materials used

And how bad is bad compost?

- Low biological diversity – usually highly bacterial above all else

- Bad smells of various pungent gases

- Still high in temperature as the actions of the thermophilic bacteria continue

- Black in colour (if it has been overheated and charred)

- Mulch like appearance with many of the raw materials obvious

- Aged materials alone do not constitute compost unless the piles of material have been built enabling air circulation and water ingress for microbes to work aerobically

fig. 01

Advanced Microbial Compost – a balanced high-quality product resulting from a thermophilic process, now ready for use. Notice the worms that have infiltrated to feed on the bacterial smorgasbord. Is used extensively in G.U. F’s Actively Aerated Compost Tea (AACT), as it contains the entire soil biological network of organisms.

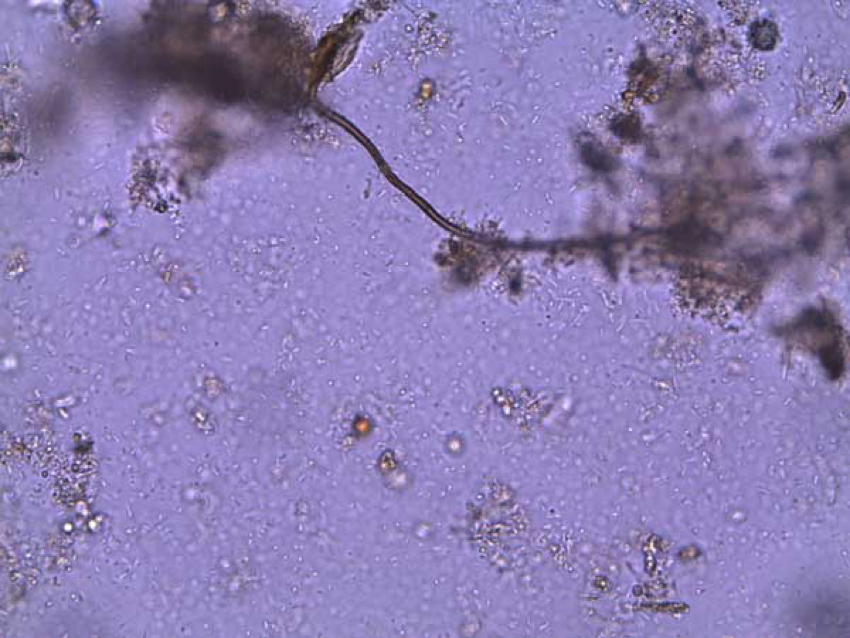

fig. 02

Poor quality compost – is unbalanced and unstable. It is still hot from the thermophilic process, verging on too dry and losing nutrients that are turning into gases distinguished by bad smells. This material does not contain a balanced soil biological network of beneficial organisms.

fig. 03

Not compost but more like mulch. This material has not been through enough thermophilic process and needs to be re started. It is high quality mulch as it contains more raw materials than it does micro-organisms and can be applied with our AACT sprayed after spreading as a helpful decomposition starter.

fig. 04

Not compost. This is woody mulch. It will potentially one day become food for micro-organisms and be broken down by the soil biological network into edible components for soil health and plant health and growth.

A History

Compost, or various interpretations of compost, have been the vehicle for plant growth and soil stability even before humans chose to cultivate the land. If the organisms that perform the degradation of dead plant material into soil didn’t exist, the planet would be covered in deep layers of litter from plants and there would be very little soil. So, with suitable environmental conditions, any once-living organic materials can be quite rapidly transformed by a suite of microbes into the most valuable plant food and soil amendment – even without human intervention. This was soon recognised by early farmers and gardeners who realised that the spent plant or animal should be returned to the soil after it was decomposed and turned into a perfect medium of highly carbonaceous humus carrying microbial diversity beyond imagination. They saw the results by the capacity to grow plants in adverse conditions as the soil was enlivened with biological inoculum, including earthworms, but did not understand that the microbes were in fact the basis upon which all life depended.

Then came modern fertilisers demanding a new paradigm as the thinking went beyond the simple application of compost or manure as a high nutrient source which of course it is not – but it is much more! The new science resolved that the major elements of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in the correct proportions were needed to create a ‘green revolution’ capable of feeding the ever-growing human population. For over 70 years, streams of research was dedicated in the pursuit of nutrient as the driving force of plant growth with high production and cosmetic appeal being the mantra above all else. Of course, much of the research was funded by the suppliers of these fertilisers and other supporting chemical inputs. An increasing number of shortcomings led primarily by environmental degradation in soils and waterways and links to human health issues over recent years have encouraged a more holistic approach. Research into soil microbiology has steadily allowed more land managers to understand that very little is known about the soil in its entirety. Even today, the most experienced soil scientists claim that what is known about soils is only 10% of what is needed to better understand how to best optimise its ongoing capacity to grow food and yet maintain a sound future fertility!

The scientific research flow is now going full circle as more effort is being made to learn about the microbial world of the soil and how this impacts on soil health and function. This is being pursued whilst still acknowledging the need to grow more plants. The past two decades have seen a keen interest in all things biological. Even traditional practices such as compost making, soils and plant management have been dissected and exposed to scientific scrutiny. This is being done to better understand the limitations of the nutrient paradigm – so entrenched in modern soil and plant management – to the best ways to transition with confidence to the holistic one which includes soil structure and life.

So, now we are back to compost with its capacity to provide most if not all nutrients, heaps of carbon (humic compounds) and all the microbes ever known that each play such vital roles in the soil biological network. Forget the promise of a few microbes in a bottle – a half average compost will host thousands of types of bacteria, many more fungi species that can be propagated and a host of protozoa and nematodes each with important beneficial roles to play in a healthy functioning soil. The best is yet to come as the exploration of such a fundamental component of the natural world in compost is better understood and managed so that the artificial band-aids of the last 70 years are gradually laid to rest.

Contact Us

Send Global Urban Forest a message